When Gates opens a gap between how something is perceived and what it is, he does not simply make a connection for the viewer — he invites self-reflection.

Installation view of Theaster Gates's Oh, You’ve Got to Come Back to the City at Gray Gallery (photo courtesy Gray Gallery, Chicago/New York)

Installation view of Theaster Gates's Oh, You’ve Got to Come Back to the City at Gray Gallery (photo courtesy Gray Gallery, Chicago/New York)

CHICAGO — Theaster Gates dissolves the boundaries between artist and collector, archivist and storyteller, ceramicist and interior decorator. These roles may seem exclusive, but they are not — as Gates has proven. The complexity of his socially engaged practice became more apparent to me after I saw three concurrent presentations of his work in Chicago: Oh, You’ve Got to Come Back to the City at Gray Gallery and Unto Thee at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago (where he teaches), accompanied by a site-specific installation on view through July 2026, African Still Life #3: A Tribute to Patric McCoy and Marva Jolly.

At the same time, certain aspects of the work gave me pause. The first is that the sum is greater than its parts. Gates is known for using such materials in his paintings as decommissioned firehoses, rubber, tar, and felt, which are linked to the legacies of racial injustice and his own life (his father was a roofer). Instead of exploring a subject through these materials, Gates makes them the subject. Once we make the link, which is spelled out for us in wall labels or previous texts on the artist, there is little else we need to do.

Installation view of Theaster Gates, African Still Life #3: A Tribute to Patric McCoy and Marva Jolly (2025), African reliquary, vinyl records, steel shelving, sound system designed by OJAS, record player (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)

Installation view of Theaster Gates, African Still Life #3: A Tribute to Patric McCoy and Marva Jolly (2025), African reliquary, vinyl records, steel shelving, sound system designed by OJAS, record player (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)My second takeaway is that Gates can aestheticize anything — something he shares with Marcel Duchamp — and he is brilliant at it. And yet, there were times I felt dissatisfied as I looked at the two exhibitions at the Smart Museum, his first institutional show in the city where he was born, raised, and has had the greatest social impact.

The site-specific installation, African Still Life #3: A Tribute to Patric McCoy and Marva Jolly, is located outside the main gallery space. Industrial steel shelving spans the entire wall between its two entrances, rising almost to the ceiling. On the shelves are collections of vinyl records and African artifacts, as in stools carved from a single piece of wood. Off to the side is a custom sound system, designed by OJAS (artist/designer Devon Turnbull), with two speakers. By preserving and displaying things that could be sold on eBay or otherwise discarded, Gates invites viewers to consider the different forms that art can take. Yet with only the spines of the records visible and the dozens of African artifacts nearly identical, the whole display feels flattened.

Installation view of Theaster Gates: Unto Thee at the Smart Museum of Art. Left to right: "Painting for My Father" (2023), "Roof Portrait" (2024), and "Defend the Black Community" (2025) (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)

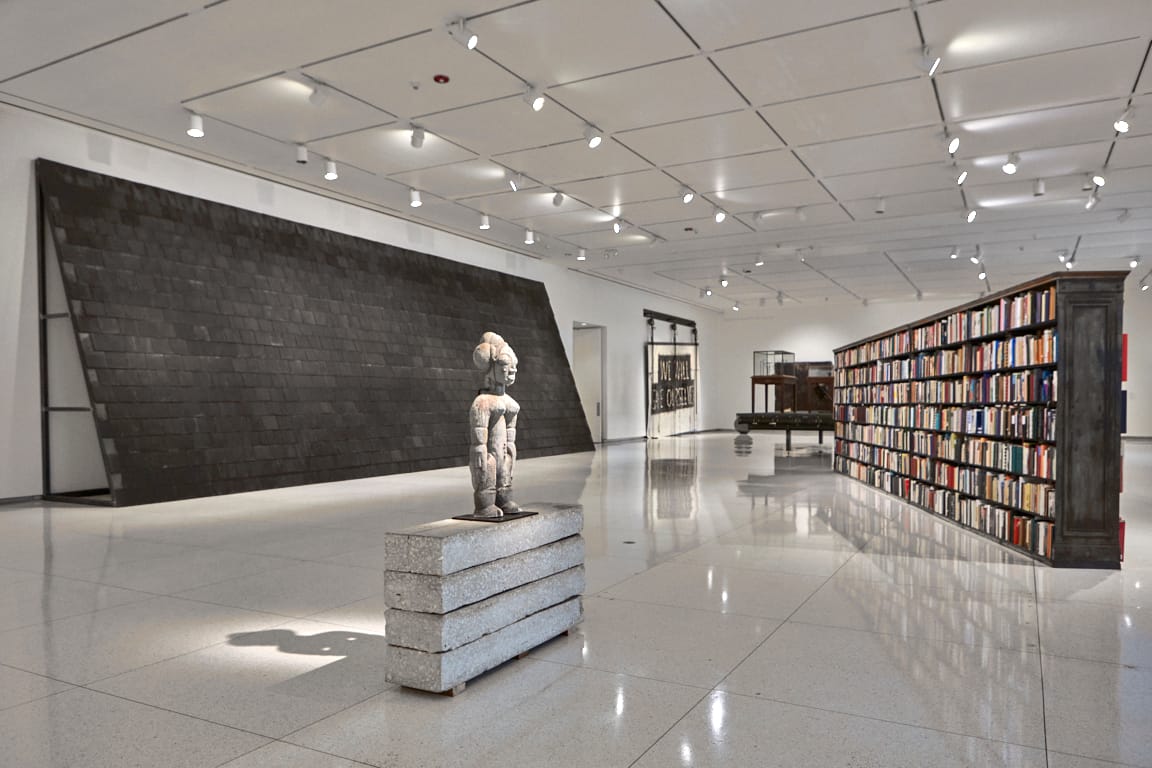

Installation view of Theaster Gates: Unto Thee at the Smart Museum of Art. Left to right: "Painting for My Father" (2023), "Roof Portrait" (2024), and "Defend the Black Community" (2025) (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)Gates pushes the conundrum further in Unto Thee, which takes up the museum’s largest gallery, and includes paintings and ceramics by the artist placed among different objects he has been given by individuals and institutions (among the latter items are a credenza, a large section of a slate roof, and a friend and colleague’s book collection).

At one point I felt like I was in a furniture showroom and Gates was demonstrating how well his tarred paintings went with the credenza. Looking at the “Robert Bird Archive,” consisting of 4,500 books, I felt like a voyeur peering into another person’s life, wondering: Did he write in the margins of his books? I wanted to see what Bird wrote in his books, but Gates prevented me from doing so. I was allowed to read only the biographer’s introduction and the book covers, and not the story of Bird’s life. These details, as small as they were, became obstacles preventing me from fully appreciating Gates’s larger project.

Installation view of Theaster Gates: Unto Thee at the Smart Museum of Art (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)

Installation view of Theaster Gates: Unto Thee at the Smart Museum of Art (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)With Oh, You’ve Got to Come Back to the City at Gray, Gates pivoted in another direction. In the main gallery of this warehouse space, he installed rows of evenly spaced, similarly sized marble columns, and placed ceramic vessels on some of them. While the columns appear to have been found, it is clear that some have been altered — for instance, cut into or sliced. There were different ways to see what Gates was up to and none of them dominated. The installation’s openness to interpretation feels very different from the didactic display of Unto Thee, where, for the most part, I felt that the connections between the items and their intended meanings or references were already made, and all I had to do was follow them.

Oh, You’ve Got to Come Back to the City shows a different side of Gates, one where there is no overarching narrative and the subject is not spelled out. On one level, he is facing off with the pioneering sculptures of the classical modernism of Constantin Brancusi. Gates’s forms are grittier than Brancusi’s, but he also arrives at them from another direction. He builds his black and slate gray clay forms, while Brancusi pared down his sleek, idealized shapes. Some of the surfaces appear to be made of stone or metal rather than clay. That ambiguity made me rethink the many associations that Gates evokes in his work, from personal narratives to Black history. When he opens a gap between how something is perceived and what it is, he does not simply make a connection for the viewer — he invites speculation and self-reflection. He also reveals the depth of his ambition and makes himself vulnerable. That’s when he attains a different kind of greatness.

Detail of Theaster Gates, "Robert Bird Archive" (2025) (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)

Detail of Theaster Gates, "Robert Bird Archive" (2025) (courtesy Smart Museum of Art)Theaster Gates: Oh, You’ve Got to Come Back to the City continues at Gray Gallery (2044 West Carroll Avenue, Chicago, Illinois) through December 20. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.

Theaster Gates: Unto Thee continues at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago (5550 South Greenwood Avenue, Chicago, Illinois) through February 22, 2026. The exhibition was curated by Vanja Malloy and Galina Mardilovich.